Welcome to 2022! In this video I look at some of the things you can be doing to ensure that you have a successful year with your portfolios and get the most from your investments.

Posts

In this new financial year we have seen state based pension schemes increase. In the UK, those with the Full UK State Pension have been given a £4.40 per week increase – over £200 per annum. This is due to the ‘Triple Lock’ which ensure the UK State Pension must rise by at least 2.5% per annum, even if wages and inflation are less than that.

Is this sustainable and/or fair?

That is a question for Politicians to debate, however, it certainly seems unsustainable when we consider how long people are now living, how much of a % of the population is working vs retired and the general cost to Governments globally of recovering from Covid (an amount that I am sure it is not yet possible to calculate completely).

So what can you do to ensure that you do not sleepwalk into poverty?

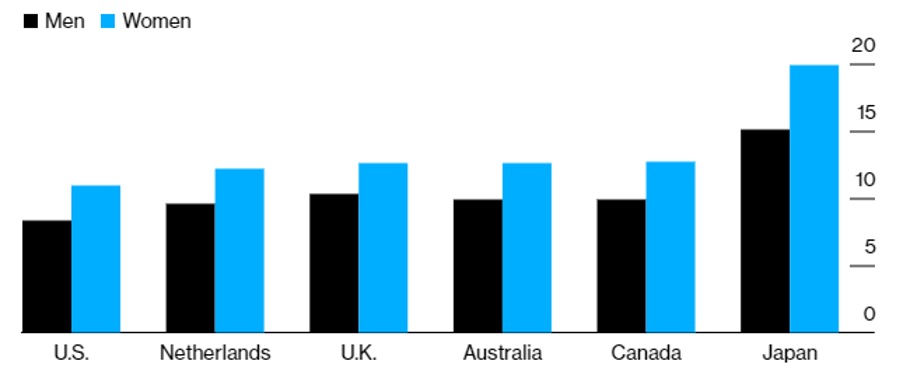

The below article shows the average number of years that people will live AFTER the point that they run out of money. At this point, they would be completely reliant upon state support. As the average age of death continues to increase and the number of centurions is predicted to rise markedly this is, in my view, one of the biggest threats to the developed world as we know it. As at now, the average female in Japan will die 20 years AFTER running out of money which surely indicates that this person is not living their best life during this period.

Responsibility has shifted over the last 2 decades or so. Final salary pension schemes are a thing of the past and the responsibility is now on YOU to save, understand, manage and calculate.

So what can you do to ensure you do not become a statistic:

- Learn. To my knowledge, financial literacy has not made it into the school curriculum in many parts of the world and I meet a number of people on a daily basis who have little to zero knowledge. A bit of knowledge regarding markets, inflation, the relationship between asset classes and interest rates etc would surely be beneficial.

- Understand. Understand the value and structure of the assets you already have. This may seem obvious yet I meet people on a daily basis who do not have full working knowledge of what they already own. The most common example of this is pension schemes – talk to me or somebody like me and get help with it if needed. There is unlikely to be a disadvantage to doing so.

- Plan. Speak to an advisor and ask them to help map out your financial future. Work out what you want, when you want it and how you want it to be structured and then let them advise you on the best way of getting there. If, for some reason, you doubt the validity of their advice (which seems to be common in the era of Dr Google) then check with another one.

Remember – nobody has ever complained because they saved too much money for their future and doing something is always going to be better than doing nothing at all.

World’s Retirees Risk Running Out of Money a Decade Before Death, By Ben Steverman

One of the toughest problems retirees face is making sure their money lasts as long as they do.

From the U.S. to Europe, Australia and Japan, retirement account balances aren’t increasing fast enough to cover rising life expectancy, the World Economic Forum warns in a report published Thursday. The result could be workers outliving their savings by as much as a decade or more.

“The size of the gap is such that it requires action” from policymakers, employers and individuals, said report co-author Han Yik, head of institutional investors at the World Economic Forum. Unless more is done, older people will either need to get by on less or postpone retirement, he said. “You either spend less or you make more.”

In the U.S., the forum calculates that 65-year-olds have enough savings to cover just 9.7 years of retirement income. That leaves the average American man with a gap of 8.3 years. Women, who live longer, face a 10.9-year gap.

The forum assumed retirees would need enough income to cover 70% of their pre-retirement pay, and didn’t include Social Security or other government welfare payments in the total.

The retirement savings gap is about 10 years for men in the U.K., Australia, Canada, and the Netherlands, the forum says. Longer-living women in those countries face an extra two to three years of financial uncertainty.

Retirement Savings Gap

Estimated years of life expectancy past retirement savings, by country.

Estimated years of life expectancy past retirement savings, by country. Source: World Economic Forum

Most of the world’s retirees are doing well compared with those in Japan, where the retirement savings gap is 15 years for men and almost 20 years for women.

While Japanese workers save no less than others, they tend to invest in very safe assets that produce few gains over time, Yik said. As a result, average savings in Japan are only enough to cover 4.5 years of retirement.

Meanwhile, life expectancy at birth for Japanese women is 87.1 years — the highest in the world, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development — and 81 years for men.

Across the world, governments and employers have pushed more responsibility for retirement onto individuals, by shifting from traditional pensions to defined contribution plans, mostly known as 401(k) plans in the U.S.

“All the risks that governments and employers used to have, we’ve shifted that onto workers,” Yik said.

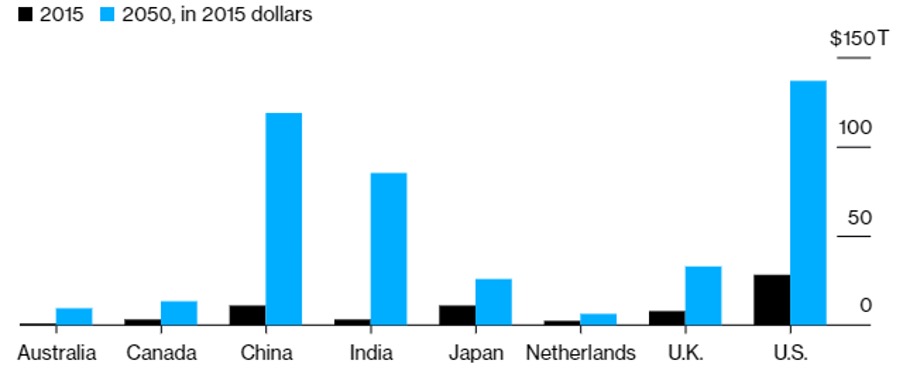

The size of the world’s collective retirement savings gap could exceed $400 trillion by 2050, up from $70 trillion in 2015, according to the report. The U.S.’s savings gap will be the largest at $137 trillion, followed by China at $119 trillion and India at $85 trillion.

Widening Global Shortfall

Total retirement savings gap by country.

Total retirement savings gap by country. Source: Mercer analysis for the World Economic Forum

Among the forum’s recommendations are making sure more workers are covered by retirement plans on the job. Employers should be doing more to improve investment options while pushing workers to save a sufficient amount of their income, according to the report.

Fewer than half of the 1,900 retirement plans served by Vanguard Group automatically enroll workers, according to the firm’s “How America Saves 2019” report released Tuesday. That number has risen quickly, however, doubling to 48% last year from 24% in 2009.

What Others Teach Us, Lessons In Investing

Lawrence Burns, Deputy Manager of Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

A conversation remains stuck in my head from early 2020, when the terms ‘lockdown’ and ‘social distancing’ were largely unheard of. My meeting with a Chief Investment Officer was coming to an end. We were discussing Tesla, which at the time was finally being recognised by the market and thus being rewarded with massive share price growth. He leaned across the table and said, “tell me you have been selling your shares.” What struck me was not his belief that we should sell, rather that he appeared to hold it with such absolute certainty. His assertion wasn’t anything to do with the company itself, but rather the ingrained belief that when a share price goes up a lot, you should sell. This was common sense. To do different would be foolish, greedy and undisciplined.

It is a conventional wisdom that pervades much of the financial industry. As the old saying goes ‘it’s never wrong to take a profit’. There is some validity in this approach, hence why it pervades and endures. A client is unlikely to be unhappy or indeed notice if you sell a stock that subsequently goes up significantly. That loss – of foregone upside – is not captured in performance data, but perhaps it should be. On the other hand, if the stock in question continues to be held and goes in the other direction it will become a clear detractor in performance data and you should expect to be asked, if not chastised, about it. And so, from the investment manager’s point of view, perhaps it can be said that it is never wrong to take a profit.

But what, I hope you ask, about the client? For the client, equity investing is asymmetric, the upside of not selling is near unlimited, while the downside is naturally capped. Surely, for the client it can be very wrong to take a profit? This goes to the heart of why so much of investing is wrong. Sadly, as an industry, institutional money managers too seldom try to get investment right for investors. Most conventions and practices exist to serve, protect and enrich investment managers’ interests.

The realities of investment therefore are often very different from the dogma. At Baillie Gifford, we are fortunate to be informed by a range of thinkers from outside our industry that have no incentive to prop-up the myths of investment management. Instead, they deal in observable facts, not the self-serving mantras beloved by professional investment bodies. This note tries to share a few of their perspectives that have been crucial to how we invest and, in the process, demonstrate that it is often not just wrong to take a profit, but it can be the worst possible mistake.

PROFESSOR HENDRIK BESSEMBINDER

WHERE RETURNS ACTUALLY COME FROM

Let’s take Bessembinder’s paper Do Stocks Outperform US Treasury Bills? as our starting point. We have all been told the answer is yes because stocks carry significantly more risk, so, of course the factual answer is no. Nearly 60 per cent of global stocks over the past 28 years did not outperform one-month treasury bills.

Equity investing as a whole though is thankfully still worthwhile. This is because of a small number of superstar companies. Bessembinder notes that a mere 1 per cent of companies accounted for all of the global net wealth creation. The other 99 per cent of companies were, it turns out, largely a distraction to the task of making money for clients. The capital asset price model (CAPM) so beloved by the financial industry is therefore nonsense because the normal distribution of stock returns that underpins it is imaginary.

This should shake the very foundations of the investment industry. It provides not an opinion but a collection of facts as to where returns come from and what investors should focus on. The entire active management industry should be trying to identify these superstar companies since nothing else really matters. Investing is a game of extremes.

But, here lies the problem, it requires a vastly different mentality to that displayed by the financial industry today. It requires focus on the possibility of extreme upside, not the crippling fear of capped downside. This requires genuine imagination should there be any hope to grasp the potential of superstar companies. After all, it required imagination to see that Amazon could become more than an online bookseller or that Tesla could become more than a premium electric car company.

In addition to imagination, Bessembinder makes it clear that it is the long-term compounding of superstar companies’ share prices that matters. Investing thus requires patience. This comes in two forms. Firstly, patience when things go wrong because even for superstar companies, progress is rarely a straight line. Many of our most successful holdings have had drawdown periods of 40 per cent. NIO was at one point down 85 per cent. It is important to not allow volatility to bully you out of a superstar company. The second type of patience is when things are going well. After all, the point of superstar companies is that they can go up five-fold and then go up five-fold again. If you sell after the share price merely doubles, crow and take your profits, you undermine the whole point of identifying companies with extreme return potential in the first place.

Let’s take a practical example. In early 2000, the founder of SoftBank, Masayoshi Son, made what may have been the greatest investment in history. He invested $20m in a Chinese ecommerce company. Two decades later his remaining investment is worth in excess of $180bn. A wonderful example of an extreme return.

Bloomberg Pictures of the Year 2019: Extreme Business. Masayoshi Son, chairman and chief executive officer of SoftBank Group Corp.

This is a well-known story and one I’ve been lucky enough to be told first-hand by Masayoshi Son. However, less well-known is the story of Goldman Sachs. Goldman invested in the same company a year before Son on far better terms. Shirley Lin, who worked for its private equity fund, had an agreement to invest $5m for a 50 per cent stake. Ultimately though, they opted to invest $3m. Five years later their stake was worth $22m, a seven-fold return. At this point, the decision was taken to sell under the guise it’s never wrong to take a profit. In many ways, this was a remarkably successful investment, until you realise that today those shares would be notionally worth more than $200bn before dilutions are taken into account.

It would seem Goldman Sachs got the identification, and perhaps even the imagination part, right. They spotted one of the greatest superstar companies of our era early on. Yet, when asked why Goldman Sachs sold, Shirley gives a depressing but predictable answer: “they wanted quicker results”. Though this example is extreme and straddles public and private ownership, the point is clear: in investing, it is often not only wrong to bank profits, it can be the worst mistake you make. Despite this, in almost every client meeting I am asked about our sell-discipline. No one has ever asked me about our hold-discipline, which is a shame, as the greater cost to clients’ returns comes from the inability to hold onto superstar companies when their returns are ticking upwards. Investment managers are usually very good at selling. This doesn’t mean the answer is never to sell but rather to take such decisions very, very carefully. To sell too early can be catastrophic and far more costly than holding on too long.

PROFESSOR BRIAN ARTHUR

INCREASING RETURNS TO SCALE

The notion that companies can even produce such extreme returns goes against much of economic theory which exhibits an overzealous equilibrium-mindset that likely has deep religious and spiritual roots. This mindset is the progenitor of a mindset of a different name common in finance, namely a belief in ‘reversion to mean’.

Bessembinder’s data falsifies the assumption that company returns quickly stabilise. Moreover, he shows when looking at nearly a century of US stock market returns the concentration of wealth creation is becoming yet more skewed towards a small number of companies. The returns are becoming extreme. The superstar companies are becoming more super.

This is particularly odd given that economics focuses on diminishing returns to scale. It takes the work of Professor Brian Arthur of the Santa Fe Institute, to understand that this concept is rooted in observing the returns to scale of the “bulk-processing, smokestack” industrial companies of the 19th century. He notes that western economies have shifted “from processing of resources to processing of information, from application of raw energy to application of ideas”. Far from diminishing returns, today’s knowledge-based companies tend to exhibit increasing returns to scale and so, in the digital era, reversion to the mean is even less common. Returns are yet more extreme.

Professor Brian Arthur. © Corbis Historical/Getty Images.

PROFESSOR MING ZENG

NETWORK COMPANIES UNLEASH UNIMAGINABLE SCALE

Brian Arthur came up with this early explanation of emerging economic reality on America’s west coast, while observing both Silicon Valley and the rise of Microsoft further north. However, as with most things today, if we wish to better understand the economic reality of tomorrow, we must look east. To help us here we have the academic Ming Zeng. He became Alibaba’s Chief Strategy Officer in 2006, a job he took to further his studies by giving him a ringside seat to history in the making.

For Ming, the greatest superstar companies of the future will be what he calls “smart businesses” harnessing network coordination and data intelligence. These organisations will look less like a company and more like a network. He notes:

The old, diversified conglomerate was like a complex machine of the old industrial age. It collapsed when it reached a certain complexity. But the future of business is more biological rather than mechanical… an ecological system grows and becomes more and more sophisticated, even more robust when it becomes richer and more diverse.

Network companies, such as Amazon, Lyft or MercadoLibre, coordinate millions of entrepreneurs, guiding them with data intelligence in real-time so both the network companies and entrepreneurs can adapt to conditions instantly in ways traditional companies could never have dreamt. This marries the benefits of enormous scale with rapid adaptability. Moreover, the larger these network companies become, the more data they have and thus the more intelligent and effective the network can become. If Ming is right, then it is logical to assume the importance of superstar companies will grow even further with the application of machine learning.

IMG

MARTIN VAN DEN BRINK

EXTENDING MOORE’S LAW

Despite the above, we must not forget that the prevalence of new superstar companies will be determined by the amount of economic and social change that takes place from here. Indeed, I would go further still and posit that the single greatest determinant of whether returns will swing from growth to value is whether the pace of change in the world increases or decreases. For it is change which creates new markets and disrupts old ones. It is change that fuels the rise of superstar companies.

We therefore need to believe the conditions for change will persist. To give us that conviction we have Moore’s law. The observation and projection made by Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel, that, for the same price computing power would double every 24 months. This projection has now become seen as a law, given its predictive power over the last 50 years. In doing so it has set the pace for the semi-conductor industry and thus for human progress.

What this means is that come the early 2030s computing power should be at least some 60x more powerful than today for the same cost. The implications of such a large increase are difficult to imagine. At the very least, the disruption should spread from industries like advertising and retail to those of even greater importance such as healthcare, finance, education, and many more.

Nevertheless, it would of course be wrong for us to have confidence in past patterns, however long and persisting, without due cause. Here we are very much helped by the insights of Martin van den Brink, ASML’s Chief Technology Officer, whose lithography machines have been largely responsible for extending Moore’s law in recent times. Van den Brink makes two points. First, that Moore’s law is older than we think. It dates back not 50 years but an entire century in all but name to when computing power was vacuum tube rather than transistor based. His second point, is even more significant and far reaching, because he believes ASML already has the technology roadmap in place to ensure Moore’s Law extends into the 2030s.

It therefore perplexes me why with the power and predictability of Moore’s law, our industry decides instead to focus far more on what interest rates or GDP growth rates mean for investing. Frankly, I think we would all be much better investors if we concentrated on the future implications of Moore’s law. A 60x increase in computing power will profoundly shape our world. The question we must grapple with is what this new world will look like.

MASSIVE OVER DIVERSIFICATION

If we follow the facts and focus on superstar companies as the only real creators of value in long-run equity returns, then it also follows that portfolios need to be constructed radically differently. Given superstar companies are by their definition very rare, this makes concentration a logical response.

The case for concentration is well made in several academic studies. Yeung et al (2012) looked at nearly 5,000 funds and found that the top ideas in these portfolios consistently outperformed the diversified funds from which they were derived. Similarly, Best Ideas by Cohen, Polk and Silli (2010) highlighted that the top 5 per cent of fund managers’ ideas are consistently the best performers across portfolios, a point that is well supported by our own experience. The authors provocatively argue that stocks added ostensibly for risk control reasons are not just a mistake but a cynical exercise in enabling investment managers to add assets well beyond their alpha-generating capabilities. Our guess at the motivation for fund managers to diversify is somewhat different, but hardly better. We think investment managers embrace adding stocks so they can diversify their own business risk from the inherent volatility that comes with stock picking.

This raises a key question for institutional portfolio construction. Whose risk are we really trying to diversify? It can only rationally be that of the investment manager. For whilst the investment manager may have a few portfolios at most, the client often has many. Indeed, I have yet to meet a client for whom our portfolio represents their entire equity allocation. The investment manager therefore benefits from the diversification within their portfolio, not the client. They already own many thousands of stocks. The real problem for the client is not lack of diversification, but radical over-diversification.

If we combine this with what we know from Bessembinder, the client has two means by which they might capture the tiny number of superstar companies that have the potential to be meaningful for long-term returns. Pay low fees to own the index and never miss out on superstar companies but have them heavily diluted. Or, attempt genuine concentrated stock picking of superstar companies that actually justifies active fees. The middle ground between those two options too often risks serving investment managers, not the clients, providing only the worst of both worlds – active fees for index-like returns.

CONCLUSION

Finally, we should return to our opening and that conversation back in early 2020. The progress of Tesla since then has shown that we were wrong to hold. We should have added substantially. Of course, this shows that one never can be certain about the future. It is only through the brilliance of minds such as those noted here that we can start to grasp what actions and approaches might be most advantageous for our clients. This goes for building relationships not just with academics and scientists but corporate visionaries as well. It was the chance to talk to that company’s CEO to hear the ambition and vision that made it clear, though not certain, that the possibility of extreme upside was there.

RISK FACTORS AND IMPORTANT INFORMATION

The views expressed in this article are those of Lawrence Burns and should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect personal opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in March 2021 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

Any stock examples and images used in this article are not intended to represent recommendations to buy or sell, neither is it implied that they will prove profitable in the future. It is not known whether they will feature in any future portfolio produced by us. Any individual examples will represent only a small part of the overall portfolio and are inserted purely to help illustrate our investment style.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this article are for illustrative purposes only.

This article contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the FCA.

There have been lots of articles on line recently saying that the traditional 60/40 portfolio is dead and that investors need to rethink their strategy.

This has been largely due to the sudden rise in treasury yields causing bonds markets to experience volatility.

However, we’re talking about a strategy that has held firm for longer than most investors have been alive, so should we just drop it after a few weeks /months of rising treasury yields?

My view is ‘no’.

Remember the following?:

- Inaction is often the best course of action

- History is not necessarily a guide to the future, but the world has been through economic shocks before

- The 50/50 chart we have looked at previously shows that time is your friend

- Don’t try to time the market

Scorned 60/40 Model Finds Allies in Biggest Test Since 2016

By Emily Barrett

The 60/40 portfolio saw investors through the cataclysm of the pandemic. The global recovery is now proving an even tougher test.

The strategy — an investing stalwart since it arose from Harry Markowitz’s Modern Portfolio Theory about a half-century ago — was already under pressure from the historic decline in bond yields. But the sharp move in the opposite direction is a more immediate threat, as recent market volatility has triggered tandem declines in stocks and bonds.

That jeopardizes the relationship at the heart of 60/40, which relies on the smaller, fixed-income allocation cushioning losses when riskier assets slump. The prospect of a faster economic recovery due to vaccines and heavy government stimulus has hit bonds hard, driving yields up at a speed that’s roiled equity markets. The method now faces one of its most severe tests since 2016, when U.S. President Donald Trump’s election raised expectations that lower taxes and lighter regulation would turbo-charge growth.

Portfolios based around 60/40 performed in 2020, with Bloomberg indexes tracking global and U.S. models providing returns of 14% and 17%, respectively. That hasn’t silenced calls to rethink or abandon the strategy, which mounted after losses in 2018. Cathie Wood recently suggested adding Bitcoin as a hedge against inflation.

Still, the strategy has some prominent defenders.

“If anything, the selloff you’ve seen year-to-date gives you a better entry point for fixed-income in portfolios,” said Erin Browne, multi-asset portfolio manager at Pimco in Newport Beach, Ca. “I don’t think by any means that the negative correlation between stocks and bonds has disappeared, or made bonds less relevant in multi-asset portfolios.”

The performance this year underscores the strategy’s resilience. The euro area, Japanese and Canadian 60/40 strategies tracked were up 3% or more year-to-date as of March 15. The global and U.S. indexes were both up more than 1.5%.

“We’re not talking about what’s the best possible return on your money — that’s another conversation,” said Kathy Jones, fixed-income portfolio strategist at Charles Schwab in New York. She pointed out that a balanced portfolio is defined as capital preservation, income generation and diversification from stocks and other risk assets.

Inflation Link

The correlation that matters is the tendency of bonds to weaken, driving yields higher, as stock markets climb — and vice versa. That positive link between yields and stocks has held since the turn of this century with only minor interruptions, in large part because of benign inflation.

That relationship would only break down if there’s a regime shift in inflation expectations, which major central banks have succeeded in keeping anchored for decades, said Brian Sack, director of global economics for the D.E. Shaw Group. The firm threw its weight behind the hedging power of Treasuries in a paper released last month.

IMG

The paper argued that U.S. government securities acquitted themselves well in the big test of the risk-asset drawdown in March last year. German and Japanese bonds were less effective, because their sub-zero yields created a situation where they were “meaningfully impaired as hedging assets.” A similar fate is looking less likely for Treasuries after recent volatility steepened the U.S. curve, Sack said.

“The rise in yields, if sustained, would provide more room for yields to fall in the future in response to a negative shock,” he said.

After all of the hype and excitement surrounding GameStop, silver and Ripple in the last few days I thought it would be interesting to discuss the differences between investing and gambling.

I am going to try to break it down into a few key areas of difference:

-

- Time. Investing tends to be for the long term because that is how long it takes to get the desired outcome. Look at a chart of the S&P 500 over 90(+) years and you can see that there have been sustained lows as well as highs but that, in time, returns have been positive. Gambling tends to be looking for quick wins ie a casino or a horse race don’t last long yet returns can be high. It is possible to make very big returns in a short time by buying a stock, however, equally, it is possible to make large losses too.

Timeline of the S&P 500 Over 90+ Years

- Knowledge. The GameStop frenzy saw some people make a lot of money and, at the beginning, was portrayed as novices who had struck gold. In fact, some of the people making big returns there were not novices at all and knew exactly what they were doing. They went into the trade with knowledge of the system, knowledge of the market, knowledge of the reality behind a short and knowledge of when to pull out.

- Having a System. If you are buying stocks because you heard it was beneficial and all your friends do it then the chances are you don’t have a system. Investors tend to have a system that they use in order to achieve great results over time. For most investors this is using a system called ‘dollar cost averaging’ whereby money is dripped into the market at regular intervals – if you consider pension funds which most people contribute to on a monthly basis this would be a good example. Dollar cost averaging mathematically smoothes volatility over time by ensuring that you buy the average price of the market over the years.

- Emotion. Investing over time is likely to be deemed rather boring by most. Buying a well diversified basket of stocks either directly, through an ETF or through a fund or a mix of all with the intention of holding it for 30 years or more is not exactly thrilling. I try to make it more interesting for clients by dotting more interesting holdings around the edges however, in reality, it is what it is. Gambling, however, can give fantastic highs and lows. If you are chasing these emotional whirlwinds through the stock market then it is likely that you have used it as a tool to gamble – particularly if your view is short term, you have no system and your knowledge level is poor!

- Time. Investing tends to be for the long term because that is how long it takes to get the desired outcome. Look at a chart of the S&P 500 over 90(+) years and you can see that there have been sustained lows as well as highs but that, in time, returns have been positive. Gambling tends to be looking for quick wins ie a casino or a horse race don’t last long yet returns can be high. It is possible to make very big returns in a short time by buying a stock, however, equally, it is possible to make large losses too.

The below article appeared in The Financial Times last year following the rise of the markets from March to September and looks to discuss some of the differences between gambling and investing:

Investing vs gambling: A fine line to tread

Financial Times

Some platforms promote investments that carry a considerably higher level of risk.

There’s no doubt that investing can be exciting. A quick win on the markets can make you feel buoyed up and hooked on finding the next opportunity. But there’s a fine line between investing and gambling and you need to be sure you’re on the right side of it.

In March, stocks globally fell at least 25 per cent — and 30 per cent in most G20 nations (though they later recovered much of the lost ground). Then we entered lockdown — a period of home isolation and, for those not furloughed, surplus spending income. A combination of eating at home, a shuttered hospitality industry and barriers to overseas holidays translated into big savings, with the Office for National Statistics revealing that we saved £157bn in just three months.

But many people did not just put it into the bank. Under lockdown there was a striking rise in the number of 25 to 34-year-olds discovering investing. Novice investors flooded the markets in March and April, hoping to profit from the market lows — and perhaps relieve some of the lockdown boredom.

In the second quarter of 2020, this age group saw the strongest growth of new Isa and self-invested personal pension (Sipp) account openings with Interactive Investor, up 275 per cent and 258 per cent year on year respectively. Younger cohorts were drawn to the biggest tech stocks: Apple and Amazon featured among the top 10 stocks held by millennials on Interactive Investor in April, and exchange traded funds, the low-cost, highly tradeable collective investments.

Those buying Amazon at the start of April at $1,901 a share saw the price rise steadily to $3,531 by September 2, a gain of 85 per cent. Over the same period, Apple had an even more impressive trajectory, rising from $60 to $134, up 123 per cent. Doubling your money in a short period is undoubtedly thrilling.

The risks of buying stocks and shares — what goes up can also come down — are widely known. However, some platforms promote investments that carry a considerably higher level of risk. One is the contract for difference (CFD), a bet on short-term share price moves and a popular form of derivative marketed to amateur UK investors. A regulatory review of the market in 2016 found 82 per cent of investors lost money on CFDs. The regulator ultimately imposed stricter caps on the market to protect consumers but risks remain.

If you’ve been tempted to use CFDs, and subsequently lost or won money or experienced a “high”, you’re likely to be gambling rather than investing. And that is not a great foundation for financial security.

The difference between investing and gambling isn’t always clear cut. Both involve risking money for potential financial gain. Some professional gamblers have tried and tested systems, while some investors are actually gambling without realising it.

But my favourite explanation of the difference is in their willingness to accept risk. Are you taking just the risks you should take or are you taking more?

Would you rather have £100 or a 50/50 chance at £200? If you take the £100, you’re an investor. If you go all or nothing, you’re a gambler. Put differently, would you rather put your money under your mattress or in an extremely volatile stock that could become worthless overnight or double in value?

If you expect to double your money quickly, you are probably gambling, even if you are buying a well-known company on the London Stock Exchange rather than using CFDs or playing blackjack in an online casino.

The best investors advocate a slow and steady route to investing success, picking a well-diversified portfolio of investments from different sectors and regions to hold for the long term. Investing regular amounts on a monthly basis and reinvesting dividends are also tried and tested methods of building wealth.

I can remember a reader’s portfolio from my time as a journalist on the Investors Chronicle that was stuffed full of high-risk oil stocks. He was in his late twenties, had a few thousand pounds invested and wanted to make a million by age 40. The overly ambitious target and his get-rich-quick approach set alarm bells ringing. We recommended he have a serious rethink.

Warren Buffett, the veteran investor, was interviewed by CNBC in early 2018, at a time when many so-called investors were borrowing money to purchase stocks and cryptocurrencies or loading up on exotic investments. He warned investors about treating the stock market like a casino and instead advised patient investment in companies with products that already have strong sales and a record of delivering profits.

“A lot of people like to gamble in the stock market,” he said. “It is insane. To risk starting all over again and losing everything is madness.”

Some blame the way we teach investing at home or in the limited ways some schools teach the subject. It’s a conundrum: to get children interested in the subject we can’t make it boring.

In share-picking contests often held over the course of a few weeks or months, the winners are unlikely to be the kids who build responsible portfolios. In truth, investing should be like watching paint dry, but this is hardly going to help children develop a life-long interest in the subject. Or wean them away from Fortnite to the Financial Times.

As part of my stock market summer school, I set my daughter a challenge to get her guinea pigs to pick stocks. They nibbled at the carrots next to ITV and Lloyds Banking Group and we’ve been following their progress every week.

What I can’t do is tell a 10-year-old that we have to wait five years to find out which pet has won. Instead, my aim is to show that investments can fluctuate over the short term, and to emphasise that with real money she’d need to put it aside for a long time, and in more than two stocks. There are ways of communicating the vital lessons of investing — without creating a new generation of gamblers.

In This Article I Show You How You Can Make £500K Through Comfortable Saving Techniques That Anyone Can Do

2020 was a difficult year for many of us. But the article below from the BBC shows that, in the UK at least, lots of people were actually able to SAVE MORE. Of course, there were others who were more badly impacted. But the article quotes MoneySupermarket who suggest that TWO THIRDS of Brits saved £586 per month.

So how can that best be utilised?

1. Budget

This is the key to all financial planning. If you were planning anything whatsoever, whether you are a management consultant, a builder or in the Military as I once was you would know what your resources are, what troops you can put to task, what assets you have at your disposal. Planning your finances is the same and in order to discover that information you need a budget.

Don’t forget to include the ‘annual spends’. Holidays, Christmas presents, school fees (if applicable) are all things that we spend on less frequently. However, they need to be included in your budget.

2. Understand your goals

Speak to an advisor and work out what you want and when you want it and what you want it to look like. This will give you structure and something to work towards.

3. Choose the right vehicle

Depending upon your location, there will be lots of different options available to you. Speak to an advisor and find the best one for your circumstances.

4. Don’t over commit

Saving is a process and discipline is key. If you commit too much then you will simply stop doing it and that is the very worst possible outcome. Half what you think is achievable and then probably use less than that. Through that methodology there should never be a reason to stop as cash should continue to build.

5. Pay yourself first

Your goals are a bill that need funding. Treat them like every other financial obligation that you pay such as mortgages, car repayments, pensions etc.

6. Take advice

Of course I am biased, but advisors will guide you throughout the process. It is long, there will be bumps in the road and it may not always go as you planned, however, the advisor should be that sound board for you to check everything with whenever you need and ensure that everything is on track for you.

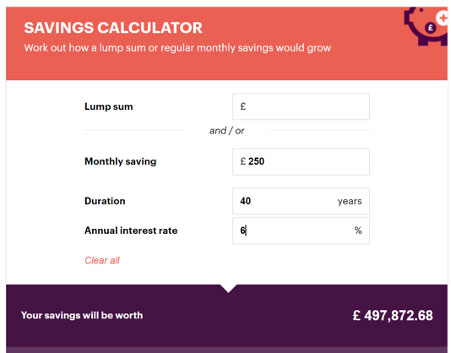

Below we can see a chart from ‘This Is Money’ showing the maths of what saving £250 per month for 40 years could look like if it grew at 6% per annum. Let’s accept some points – we’re all likely to work for 40 years so that part of the maths is workable, 6% average growth per annum is fair historically and £250 is less than half what Moneysupermarket say two thirds of Brits have spare each month.

So don’t wait for tomorrow, get your financial journey started today and begin working towards a better future.

Spent Less, Saved More: What We Bought This Year

People spent less and saved more in 2020 as the pandemic led to shops, pubs and attractions being closed down.

Consumer spending was down 7.1%, says Barclaycard, which tracks almost half of all credit and debit card spending.

However spending on essential items climbed 4.1%, while independent businesses benefited as many more of us shopped locally.

Meanwhile Brits working from home saved an average £110 a week, according to a separate survey from Aldermore Bank.

“2020 has accelerated many trends,” said Raheel Ahmed, head of consumer products at Barclaycard.

“E-commerce has seen huge growth, working from home has meant many are shopping more locally and experiences within the home, such as virtual work-outs have become the norm.”

Online grocery shopping surged 70.3% over the year and looks set to have become the norm for many.

The amount we spent on fuel fell by more than a fifth – 20.3% – as we made far fewer trips, and prices fell at the petrol pump.

‘Fashion For Independants’

We also spent 15.6% less on clothing, presumably because many worked from home and there were no exciting events to go to that needed new outfits.

The Barclaycard data showed that we spent an extra 28.6% at independent food and drink shops, such as off-licences, butchers and bakeries, compared with a year earlier.

It could be another trend that’s here to stay as the card company’s consumer confidence research showed that 57% of Brits wanted to increase their support of nearby businesses as a result of lockdown restrictions.

Joh Rindom, who runs That Thing, an independent fashion, homeware and accessories shop, said perhaps because people have spent more time at home, perhaps because they’ve focused on what is important to them, this year there has been a “fashion for independents”, she thinks.

Support for florists bloomed during the year with purchases up 22.7% while spending on takeaways online surged 49.1%.

But department stores were hard hit by the change in our spending habits, with spending down 17.2%, while clothing retailers experienced a 15.6% slump, leading to the financial problems at the likes of Debenhams and the Topshop owner, Arcadia.

Saving Up

Brits’ saving habits have been boosted by the change in lifestyle during the lockdown and pandemic changes.

According to Aldermore Bank, weekly savings include £29 from not commuting, £20 on not spending as much on breakfasts and lunches, £22 on not socialising with work colleagues, £18 by avoiding takeaway coffees, and £22 on not going out on weekdays after work.

“The saving habits adopted due to the Covid-19 pandemic are likely to continue beyond this period and turn into better long-term spending routines,” said Ewan Edwards, director of savings at Aldermore.

“One positive to take from 2020 is it has given some people the opportunity to reflect on how to improve their personal finances.”

Research by Moneysupermarket suggested that two-thirds of Brits saved an average of £586 per month in 2020 – equivalent to £7,032 over the course of the year.

Londoners saved the most at £1,286 per month, followed by Yorkshire & the Humber who saved £690 and the East Midlands who saved £619. The Welsh saved the least at £302 per month.

“Some are saving more than ever as a result of no commuting fees, reduced childcare costs and far less going out for meals or day trips,” said Sally Francis-Miles money spokesperson at MoneySuperMarket.

“This is especially evident in London where travel and childcare costs are often far higher.”

‘Hard-hit’

But many have been hit hard and been unable to get into the savings habit in 2020. “Money worries are a very real preoccupation for millions across the country,” pointed out Ms Francis-Miles.

“Thousands have been made redundant or had their hours cut, they may be facing a struggle to cover the basics such as household bills and mortgage or rent payments.”

Bottom Line Up Front:

- Learn. Learn from 2020. How has your portfolio behaved so far and how did it make you feel? Volatility is to be expected with investing – but how much of it can you cope with?

- Review. Speak to your advisor and if the answer to point 1 was ‘it made me lose sleep at night’ then discuss whether you need to change things moving forward.

- Where now? Has the answer ever been any different for medium to long term thinkers?

- Opportunity. Don’t waste them. Keep some powder dry and be confident to use downturns to your advantage (easy to say and difficult to do).

The last few months have undoubtedly changed a monumental number of things that we used to do as part of the daily routine. The commute to work may well now be less frequent going forward as more and more firms realise that their staff are efficient from home. Meetings via platforms such as Zoom or Teams are the new normal potentially reducing business travel in the future. All of us got used to shopping for groceries as well as other items on line whereas previously we may have preferred to go to the store.

Who would want to be investing into city center corporate real estate at the moment? Will we see the architecture of cities change as they could feasibly become ‘fatter and flatter’ due to the requirement to go to the office less, if at all? Will offices become null and void altogether with people instead adopting a ‘shared space’ type of environment where they utilize the space for a far shorter period of time if they need to?

So where would you want to invest?

The below has been taken from an article relating to the CEO of Microsoft:

During the COVID-19 epidemic, Nadella has taken to calling the tech giant’s workforce “digital first responders.” The company’s developers and cloud experts are working side-by-side with organizations including the CDC, John Hopkins University of Medicine, state unemployment centers, retailers, and schools. Institutions “have gone through two years’ worth of digital transformation in two months,” says Nadella. “We were seeing the other side of it which is the peak demand on our infrastructure.”

So should any of this impact how or why or when we invest? Not really in my view. No human has ever been able to predict the future, albeit we can open our eyes and look to what sectors we think may fair better in certain conditions. Areas such as Cyber Security, Robotics and Automation, FinTech etc are all reasonably topical at the moment and would generally fall under the ‘tech’ umbrella. ETFs/Mutual Funds that track those sectors have grown exponentially this year. That said, great fund managers have always been good at selecting the best individual stocks so continue to let them do that and ETFs generally allow access to an index which will ‘autocorrect’ anyway ie as one stock gets larger it takes a bigger slice of the pie or if one company goes bust the next one on the list jumps into the index.

The general feeling at the moment seems to be that the market as a whole has had a poor year, the recovery since March is inexplicable and that the market will fall from here due to an inevitable second wave of Covid 19. The reality is, however, that certain companies/sectors within ‘the market’ have generated huge returns in 2020 so far and, in fact, the S&P 500 now sits only circa 1% off it’s February high.

The question, however, is would you have predicted that in January? The answer is of course that you would have been unlikely to have done so. Going forward, where would you invest? Again, this is going to be dictated by your risk profile more than your ability to predict the future.

The situation has not changed from an investment perspective, it never has. Use great fund managers and allow them to do their job. Offset this by using great ETFs to gain whole of market exposure which should never fail and ensure that there is sufficient fixed income/commodity exposure throughout to keep the volatility within a range that you feel comfortable with.

Ocado says switch to online shopping is permanent

By Simon Read, Business reporter

Online grocer Ocado says the switch to internet shopping amid the coronavirus lockdown has led to a “permanent redrawing” of the retail landscape.

Its comments came as it said sales during the first half of 2020 jumped 27% to more than £1bn.

“The world as we know it has changed,” said chief executive Tim Steiner.

“As a result of Covid-19, we have seen years of growth in the online grocery market condensed into a matter of months; and we won’t be going back.”

“We are confident that accelerated growth in the online channel will continue, leading to a permanent redrawing of the landscape of the grocery industry worldwide.”

He said Ocado was now the fastest growing grocer in the UK, thanks to a 50/50 partnership with Marks and Spencer announced last year.

As part of the deal, which saw M&S take a half-share in Ocado’s retail business, Ocado will start delivering M&S grocery products from September, when its current deal with Waitrose expires.

The group reported a loss before tax of £40.6m in the six months to the end of May, blaming an increase in investment to handle the higher demand generated as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

During the period the company opened its first two customer fulfilment centres abroad, for Casino in France and Sobeys in Canada, while increasing capacity in the UK.

- Retailers report sales jump in June

The loss was smaller than the £147.4m posted in the same period last year, although that figure included £99m of costs incurred as a result of a major fire at its warehouse in Andover.

But after raising £1bn through an equity and bond issue last month, Ocado said it had £2.3bn in cash on its balance sheet.

“There is evidence to suggest many shoppers will likely continue buying their groceries online once lockdown measures have been lifted completely, but it will be difficult for Ocado to maintain the sales registered at the peak of the crisis,” said John Moore, senior investment manager at Brewin Dolphin.

“Nevertheless, Ocado has a strong balance sheet and the Covid-19 pandemic has super-accelerated many of the trends that have led to its exceptional share price growth over the last few years, placing the company in a good position for the future.”

A new Lidl a week

Separately, discount grocer Lidl has revealed plans to open a shop a week until Christmas, creating 1,000 jobs.

The 25 new stores will be opened across England, Scotland and Wales with sites in Selhurst, Harrow Weald, Coleford and Llandudno Junction opening in the coming weeks.

By the end of 2023 it plans another 100 stores across Britain, creating 4,000 more jobs, and bringing its total number of shops to 1,000.

“It is testament to the continued hard work of our colleagues that we are able to continue forging ahead with our expansion plans, despite the challenging circumstances that have been faced over the past months,” said Lidl GB boss Christian Härtnagel.

Lidl – which opened its first shops in the UK in 1994 – has opened new stores throughout the pandemic in locations such as Birmingham, Torquay and across London.

Regular readers will know that I am a firm believer in the concept that trying to time the market is futile and that adopting a more medium-long term approach in line with a Warren Buffet style philosophy is the key to investment success.

However, media consistently bombards us with the opinion of ‘experts’ and they generally advise that we act in one way or another. Frustratingly for readers and investors, there is normally at least half of them that think one thing and the other half believing the total opposite. Furthermore, both sides will be able to ‘prove’ their viewpoint with historical data.

It is for this reason that I found the below article to be so refreshing.

One of the most successful money managers in the world who is currently responsible for a tremendous amount of invested assets quite simply saying that he doesn’t really know what is going to happen next. Finally, somebody has had the courage to hold their hands up and say that the current situation is so unlike any that we have seen before that attempting to predict the outcome is ridiculous.

He does, however, predict a recovery and that will come around the beginning of 2021 in his opinion but he does suggest that this is only a ‘best guess’.

So what should readers and investors be doing? Investing (as long as you can actually afford to)! We all know that a recovery will happen, we just can’t say with any degree of certainty exactly when. That said, we can be reasonably certain that if you have a medium – long term view then you would be buying at depressed prices at the moment

‘At current depressed price levels, people should be investing, he said. But there’s a big caveat: only if they have “secure cash flows,” which are much more elusive in the current crisis.’

But what makes this particular money manager such an authority? Why is he right and the others wrong? There are a number of reasons why I chose this article to share above all others, the main one being that he is not trying to second guess or predict what every text book will tell you is unpredictable. Regular readers will remember the article that I wrote at the end of February, 6 Tips to Navigate Volatile Markets, and you will, hopefully, notice some similarities between what this money manager is saying below and what was said within that text. You cannot time the market, and if you are fortunate to manage it successfully once, then you need to be lucky a second time to know when to buy back in. It is unusual to get lucky twice.

‘Young said his cynicism about confident market calls is born out of more than 30 years’ investment experience. Even if someone correctly times the market once, they’re unlikely to repeat the feat, he said. And bottoms, he said, are only easy to identify after the fact.

“I’m sure the market bottom, as it always is, will be obvious with hindsight,” he said. “People identify it with one particular thing that it happened to coincide with. Again, in my experience, that’s often not quite right. But it’s an easy explanation for people with hindsight. I’m afraid you never know.”

A $645 Billion Manager Says Calling the Market Bottom Is ‘A Mug’s Game’

Tom Redmond and Abhishek Vishnoi

The coronavirus market sell-off is probably past its worst, strategists at Morgan Stanley have said. Jeffrey Gundlach sees bigger losses ahead, while Howard Marks went from bearish to more optimistic in a week.

For another veteran investor, calls on whether equities have reached a bottom are nothing short of futile.

“I think it’s a mug’s game,” said Hugh Young, head of Asia Pacific at the $644.5 billion manager Aberdeen Standard Investments. “Nobody has the answer.”

Shares across the world have recovered some of their losses from the rout spurred by the virus. An index of global equities has risen more than 20% from its low in March, technically entering a bull market, though it’s still down more than 18% this year.

For Young, it’s possible markets have reached a bottom, but it’s far too early to say with certainty.

“It feels as though this is going to go on for a fair old time,” he said. “And to an extent that must be in prices. But then we’re seeing some quite sharp government action, whether it’s bank dividends or changing rules on loans, foreclosures and all sorts of things. So it’s very hard to be precise.”

Young argues that global lenders’ moves to halt dividend payments after pressure from regulators came “slightly out of the blue.” More knock-on effects of the coronavirus crisis are likely, he says, and it’s impossible for them to be fully incorporated in prices.

Aberdeen’s flagship Asia Pacific Equity Fund has fallen about 18% this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Over a three-year period, it’s beaten 66% of peers.

Young said his cynicism about confident market calls is born out of more than 30 years’ investment experience. Even if someone correctly times the market once, they’re unlikely to repeat the feat, he said. And bottoms, he said, are only easy to identify after the fact.

Hindsight Benefit

“I’m sure the market bottom, as it always is, will be obvious with hindsight,” he said. “People identify it with one particular thing that it happened to coincide with. Again, in my experience, that’s often not quite right. But it’s an easy explanation for people with hindsight. I’m afraid you never know.”

What, then, can an investor such as Young say with confidence? For one, the crisis will last for at least several more months, and many businesses worldwide will come under severe stress. There’s still a lot of pain to come through, Young said.

“Our best guess is that this year’s a write-off and then things will normalize at the beginning of next year,” Young said.

At current depressed price levels, people should be investing, he said. But there’s a big caveat: only if they have “secure cash flows,” which are much more elusive in the current crisis.

Nobody Knows

Another veteran money manager echoed Young’s view about attempting to call the low, while saying statistically there could be more pain ahead.

“No one can know if we are at the bottom in index terms,” said Mark Mobius, who set up Mobius Capital Partners last year after three decades at Franklin Templeton Investments. “We do know that historically for all markets the average bear market decline has been about 50% with a range of 23% to 70%. So if history is our guide, then we could have more to go.”

Recently we have seen significant market downturns and it has been widely reported that the FTSE 100, the benchmark index for the UK stock market, has actually had a negative return over the last two decades. So when people like me tell you that investing is a long term game and short term market volatility should be somewhat ignored (certainly expected), does this revelation not negate that argument?

On the face of it, that would certainly appear to be the case. However, what this statistic does not include, which the below article eludes to, is dividends.

So what is a dividend? A dividend is a payment made to a shareholder. If, for example, you buy shares in BP, you can expect to receive a dividend from BP and, often, these dividends can be significant. Not all companies pay dividends, often some of the large tech stocks in the US do not, however, most of the stalwarts of the FTSE 100 certainly do. Indeed, dividends are often an attractive way for investors to gain an income and there is significant pressure on CEOs of listed firms to ensure that dividends are paid to shareholders regardless of market conditions.

When we look at the performance of the FTSE 100 over the same period of time, but also include the dividends that would have been received by shareholders (total return), this significantly skews the maths back towards holding equity as a great long term wealth builder (the return moves from a negative 14% to a positive 77% over the same time frame).

One of the main issues with investors, however, is that we are all biased in one way or another. It is common for UK based investors to favour UK based stocks, this is common within pension funds for example. In order to efficiently invest for the long term, we need to be looking much wider than the UK and considering the entire globe. Indeed, the performance of the US market or the global index as a whole during the same period of time being referenced above is markedly different.

So, do not always believe the headline. It is important to speak to somebody who has a reasonable degree of market understanding and consider whether there is any information being omitted from the headline that would actually fundamentally alter the statement.

U.S. Stock Bear Markets and Their Subsequent Recoveries

By Simon Lambert

The FTSE 100 has gone nowhere in 20 years, so why are investors told to think long-term? That is the kind of question that those of us who advocate investing in the stock market as the best way to grow your wealth deserve to face.

It’s been a brutal fortnight-and-a-half for investors and the UK’s leading stock market index closed down again yesterday, against a backdrop of the Bank of England’s emergency interest rate cut to 0.25 per cent and Rishi Sunak’s coronavirus-battling Budget.

As I wrote this column last night, the FTSE 100 had just closed at 5,876.

This morning it was trading down 6 per cent at 5,551 – down 28 per cent cent on its recent high in mid-January.

More importantly though, that is 20 per cent below the 6,930 dot com boom peak on New Year’s Eve in 1999.

You can see why people dubious about the merits of risking money investing could claim the stock market has trod water for two decades, albeit they’d be slightly wrong because the Footsie’s fallen a fair bit.

But there is a case for the defence and it hinges on dividends.

There is a fundamental flaw with the way that the stock market is measured by the index of the UK’s biggest firms, the FTSE 100, and its cousins, the mid-range FTSE 250 and broader FTSE All-Share.

All of them put forward an index based on companies’ share prices, but that’s not what delivers long-term investment returns.

What is far more important is the overall reward you get from holding shares and a big chunk of that comes from dividend payouts compounded.

To measure that you need a total return index – and while FTSE compiles these for its main indices, they are not widely-published, despite the fact that you’d think it would definitely be in the London Stock Exchange or investment platforms’ interests to do so.

Take the FTSE 100 Total Return index figures and the picture over the past 20 years looks very different.

Earlier this week, I asked Russ Mould, of AJ Bell, to pull the figures for This is Money, so I could do the comparison.

On 31 December 1999, the FTSE 100 stood at 6,930, whereas when the stock market closed on Monday after its bumper 7.7 per cent one-day fall it was at 5,966 – a 14 per cent decline.

In contrast, on 31 December 1999, the FTSE 100 Total Return index stood at 12,447, whereas it closed on Monday at 22,114 – a 77 per cent rise.

Over 20 years, that is a 2.86 per cent average annual return, which in all honesty is pretty poor for two decades of investing.

It’s only slightly higher than inflation, which has been 75 per cent since the start of 2000, but you are likely to have struggled to match that with cash savings.

And, on the bright side, a 77 per cent return is considerably better than a 14 per cent loss.

It is also very important to note that if you’ve spent the last 20 years only investing in something that tracks the FTSE 100 then you are doing it wrong.

Investments should be far more diversified than just the UK’s top 100 companies, or even the broader FTSE All-Share basket that includes much more of Britain’s stock-market listed firms.

Ideally, you start at the position of owning the world, by investing in a fund, trust, or tracker than invests in companies around the planet – and then if you want a bit more UK exposure you add a small dollop in.

Those who invested in a global fund would have seen a much better return over the past 20 years than even the total return versions of the FTSE 100 or All-Share would have offered.

If you want to reassure yourself as you nervously watch stock markets plunge into the red, it’s worth remembering the total returns from this instead of dwelling on one misleading stock market index.

This is every investors nightmare isn’t it? You have just finally plucked up the courage after potentially years of other people telling you that they’ve been involved and have been getting results and then ‘boooommm’ – day one and markets fall 3-5%.

Is this actually an issue? According to Warren Buffett, arguably the most successful investor of all time, the simple answer is ‘no’. He is very clear that if you are taking a long term view then the small peaks and troughs of the normal trading environment matter very little. As can be seen in the below interview that he recently gave, when he buys a position he is doing so with a 20-30 year vision, and this is the most simple way to view the market.

As Buffett tells us below, equities will outperform any other asset class in the long term. Of that he is clear. So why do so many people get it so wrong?

In my experience this comes down to the mental positioning at the outset and the design of the portfolio that they are investing in to. If somebody is aggressive and looking for big returns, then they have to accept that they need to be willing to hold the assets for a long time, as Buffett says. The problem comes when people want the big returns in a short period of time – ‘well, the US market returned over 30% last year so I’m going to get myself involved in that to boost the house deposit that I have been saving up for and intend to lay down in one year’ – error. This person has now placed their house deposit at risk and it is highly unlikely that the US market will return 30% plus two years in a row. Further, the logic that it will do it again purely because it did so last year has absolutely no substance to it from a fundamental perspective.

Remember, in the long term, it is fundamental economics which impact the long term growth of equity markets. There will be positive days and there will be negative days throughout the duration of your investment horizon. If you are looking for a quick win then you need to get lucky or have real conviction in what you do and it needs to be done with a tiny percentage of your overall pot. If it was easy then there would be more people like Warren, however, there is only one – and his message is clear – do not change your strategy – do nothing or keep buying:

As stock futures dropped before Monday’s opening bell, Buffett said “that’s good for us.” “We’re a net buyer of stocks over time,” he said. “Most people are savers, they should want the market to go down. They should want to buy at a lower price.”

Warren Buffett interview highlights: ‘Good’ when stocks fall, likes Apple a lot, coronavirus impact

By Pippa Stevens

Warren Buffett joined CNBC’s Becky Quick with an exclusive three-hour interview on “Squawk Box” on Monday.

Below are all the highlights:

9:02 am: Long-term outlook ‘not changed’ because of the coronavirus

As the coronavirus outbreak sparks fears of a slowdown in global growth, Buffett closed the CNBC interview saying his long-term outlook remains unchanged.

“We’re buying businesses to own for 20 or 30 years. We buy them in whole, we buy them in parts … and we think the 20- and 30-year outlook is not changed by the coronavirus.”

8:59 am: Buffett says Kraft Heinz should pay down debt, maintain dividend

“I think Kraft Heinz should pay down its debt. Under present circumstances, it appears that it can pay the dividend and pay down debt at a reasonable rate,” Buffett said. “And it has too much debt, but it doesn’t have debt it can’t pay down. The debt holders are going to get the interest and the debt should come down by year-end. I think it will, and I think it can with the present dividend.”

8:57 am: Buffett says he talked to his ‘science advisor’ Bill Gates about the coronavirus

The Berkshire Chairman said he spoke to Microsoft founder Bill Gates about efforts to contain the spread and impact of the coronavirus. “Now what they hope to get is a universal flu vaccine, but that’s a long way off. It isn’t impossible. I mean I asked my own — my own science advisor is Bill Gates … I talked to him in the last few days about it and he’s bullish on the long-term outlook for a universal prevention of it.”

8:45 am: Cryptocurrency has basically ‘no value’

“Cryptocurrencies basically have no value,” Buffett said, noting that they don’t produce anything or mail investors checks. Instead, the value is derived from the belief that someone else will value the more highly in the future. “In terms of value, you know zero,” he said.

8:34 am: ‘Premium’ for buying businesses outright

As a conglomerate, Berkshire Hathaway is known for acquiring entire businesses. But recently, Berkshire has favored buying shares of companies, but not the entire entity. “There’s quite a premium,” Buffett said of buying an entire business. “Part of the premium is because you can borrow so much money so cheaply in buying those businesses.”

8:28 am: These are ‘very unusual conditions’

As the yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury sank to its lowest level since July 2016, Buffett said there are “very unusual conditions.”

“It makes no sense to lend money at 1.4% to the U.S. government, when it’s government policy to have 2% per year inflation. The government is telling you we’re going to give you 1.4% and tax you on it, and on the other hand we’re going to presumably devalue that money at 2% per year. So these are very unusual conditions.”

8:15 am: Buffett says he got a smartphone

Despite owning a large position in Apple, Buffett famously never had a smartphone — until now. “My flip phone is permanently gone,” he said.

8:11 am: It is ‘harder’ for Berkshire to buy back shares than for other companies

Buffett said it’s difficult for Berkshire Hathaway to buy back large numbers of its shares. “It’s harder to buy back Berkshire Shares than say Bank of America buying back its stock … they can really do it without moving the market.” “Berkshire is held by people that really primarily keep it,” he said.

8:04 am: Apple is ‘probably the best business I know in the world’

Apple is Berkshire Hathaway’s third largest holding behind insurance and railroads, Buffett said. He called the company “probably the best business I know in the world.” Berkshire owns roughly 5.5% of the business, he said.

7:54 am: Would ‘certainly’ vote for Bloomberg

Buffett said he would “certainly” vote for Mike Bloomberg. “I don’t think another billionaire supporting him would be the best thing to announce. But sure, I would have no trouble voting for Mike Bloomberg.”

7:50 am: Buffett says he’s a ‘card-carrying capitalist,’ but not a ‘card-carrying Democrat’

Buffett said that while he’s a Democrat, he’s not a “card-carrying Democrat” and has voted for Republican candidates in the past. As Sen. Bernie Sanders surges in the polls, Buffett said, “we will see what happens” regarding the Democratic nominee. Buffett did say that he’s a “card-carrying capitalist.”

7:41 am: Buffett says Berkshire is worth the same with or without him

In recent years there have been questions about what happens at Berkshire Hathaway in the era after Buffett, who is 89. “Berkshire without me is worth essentially the same as Berkshire with me. My value added is not high, but I don’t think I’m subtracting value,” he said.

7:38 am: Buffett says bank stocks are ‘very attractive compared to most other securities’

“I feel very good about the banks we own. They’re very attractive compared to most other securities I see,” Buffett said. Banks are a big part of Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio, which is worth more than $248 billion. Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, BNY Mellon, and U.S. Bancorp were all among Berkshire’s 15 largest stock holdings.

Correction: An earlier version misstated Buffett’s title. He is chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway.

7:32 am: Wells Fargo shareholders would be ‘a lot better off’ had company addressed problems sooner

Berkshire has been selling its stake in Wells Fargo, and Buffett said the bank is a “classic in terms of one lesson,” which is that the company should have attacked its phony accounts scandal “immediately.” “They had an obviously very dumb incentive system,” Buffett said. “The big thing is they ignored it when they found out about it.” Buffett said shareholders would be “a lot better off” if the bad practices weren’t ignored, which was a “total disaster.”

7:20 am: ‘Would not be a profit’ if Berkshire were to be split up

While some have said that Berkshire Hathaway’s businesses could be more profitable if the conglomerate were to split, Buffett said that would actually be bad for business. “You can have spinoffs … you cannot dispose of the entire business without having very substantial tax liabilities,” he said. “It would not produce a gain. Having them together, however, produces very valuable synergies.”

“There would not be a profit if we were simply to announce that over the next 24 months you could come in and buy any business we had and we would sell to the highest bidder,” he added.

7:13 am: Coronavirus outbreak shouldn’t affect what investors do with stocks

Buffett said that while the coronavirus outbreak is daunting for the human race, it shouldn’t impact investors’ portfolio decisions. “It is scary stuff. I don’t think it should affect what you do with stocks, but in terms of the human race it’s scary stuff when you have a pandemic,” he said. Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting is May 2, which Buffett said the coronavirus could “very well” impact.

7:05 am: Buffett warns that ‘reaching for yield is really stupid’

The Berkshire Hathaway chief said that investors should not reach for yield beyond their risk-tolerance, even with interest rates so low and stocks seemingly like the only place to get a return. “Reaching for yield is really stupid. But it is very human,” he said, delivering sobering advice to folks near or in retirement. “People say, ’Well, I saved all my life and I can only get 1%, what to do I do? You learn to live on 1%, unfortunately.”

7:00 am: Berkshire’s cash pile stands at $128 billion, we’d ‘like to buy more’

Berkshire Hathaway’s cash balance now stands at $128 billion, leading some investors to question why the Oracle of Omaha hasn’t put the firm’s war chest to work. “We’d like to buy more,” he said, after being asked about his cash on hand.

6:55 am: Buffett says American public going ‘wild’ with enthusiasm for index funds

As passive investing becomes more and more popular, Buffett likened index funds to conglomerates, saying the American public is going “wild” with enthusiasm for passive investing. “You buy 500 businesses all put together, and I mean that’s the ultimate conglomerate.”

6:46 am: Buffett says economy is ‘strong,’ but a ‘little softer’ than 6 months ago

Buffett said that while the U.S. economy still looks healthy, it isn’t as robust as it was even half a year ago thanks to a combination of global headwinds. “It’s strong, but a little softer than it was six months ago, but that’s over a broad range,” he said. “Business is down but it’s down from a very good level,” he added.

6:39 am: Buffett won’t reveal why he sold Wells Fargo

Berkshire Hathaway sold some of its Wells Fargo position in the fourth quarter, filings revealed, but when Buffett was pressed for why the firm decreased its position he wouldn’t reveal why. “We’ve bought Bank of America and sold Wells Fargo,” he said.

6:25 am: ‘Very significant percentage of business’ impacted by coronavirus

As the coronavirus outbreak hits stocks, Buffett said, “a very significant percentage of our businesses one way are affected.” He added, however, that the businesses are being affected by a lot of other things, too, and he said the real question is where those businesses are going to be in five to 10 years. “They’ll have ups and downs,” he said.

Specifically, he pointed to Apple and Dairy Queen being hit, as well as carpet maker Shaw Industries.

6:19 am: Buffett says he’s bought stocks every year since he was 11

Buffett said that no matter what’s going on in the market, he’s always been an overall net buyer of stocks. “I’ve been a personal net buyer of stocks ever since I was 11, every year.”

“I haven’t bought stocks every day. There have been a few times where I thought stocks have been quite high, but that’s very seldom” he added.

6:11 am: Don’t buy or sell ‘based on today’s headlines’

As volatility in the market increases because of the coronavirus, Buffett said not to make investing decisions based on day-to-day moves. “You don’t buy or sell your business based on today’s headlines. If it gives you a chance to buy something you like and you can buy it even cheaper, you’re in good luck,” he said, adding that “you can’t predict the market by reading the daily newspaper.”

6:06 am: ‘That’s good for us,’ Buffett says of dropping stocks

As stock futures dropped before Monday’s opening bell, Buffett said “that’s good for us.” “We’re a net buyer of stocks over time,” he said. “Most people are savers, they should want the market to go down. They should want to buy at a lower price.”

CNBC’s Tom Franck, Michael Sheetz and Matthew Belvedere contributed reporting.

Any more questions? Feel free to get in touch!